Starting with the 1.86 release, the Tailscale client can encrypt its state file while it is stored on disk. This makes it harder for attackers to potentially “clone” your nodes to other machines, or otherwise mess with the settings of your client. This blog post is a deep dive into how Tailscale state file encryption works under the hood.

What’s in the state file?

The Tailscale client has a bunch of state it needs to persist, including:

- The machine private key, which is used for Noise connections to the coordination server

- Node private keys (WireGuard keys) for each tailnet you’re logged in to

- Tailnet Lock private keys for each tailnet

- Client settings for each tailnet, such as what exit node to use, or whether to enable auto-updates

What we really care about here are those private keys stored in the state file, since those are used to identify your node to the coordination server and to other nodes. We need to protect them from exfiltration.

Threat model

First of all: What are we worried about?

If attackers come through the public Internet or your local network, then your device running Tailscale should be reasonably safe (unless there’s a vulnerability in other software, or the OS). Encryption at rest makes no difference here because we use public key cryptography: neither the keys nor the data we send over the network can leak to outside observers.

If an attacker did manage to get a foothold on your device, now we’re in trouble. All tailscale state files are owned, and only readable, by root (or “Administrators” on Windows, but we’ll just use “root” as shorthand). So an attacker with read access to the filesystem as root can read the contents of Tailscale’s state file, and copy it off of your device.

If the Tailscale state file is unencrypted, an attacker with that kind of root access could use the file’s contents from a different machine and impersonate your node. From the perspective of the Tailscale coordination server, it’s as if your device switched to a different network and got a new IP address. We call this attack “node cloning”.

Note that as long as the attacker maintains root access to the compromised machine, they can make requests on behalf of the Tailscale node, regardless of anything we do. Node cloning only becomes a problem if the attacker gets locked out of the compromised machine, like after you detect and remediate the initial compromise.

The obvious solution is to encrypt the state file and make node cloning harder, and that is exactly what we’ve built. This protects against:

- A compromise where an attacker can read files from disk as root (e.g. path traversal vulnerabilities), but cannot execute arbitrary code

- A simple infostealer that scans the filesystem for anything that looks like credentials, but doesn’t have custom logic to parse and decrypt the Tailscale state file

But note that state file encryption does not protect against attackers (or malicious insiders, or very clever employees) that can:

- Read process memory (where our decrypted keys live at runtime), or

- Execute code as root, to decrypt the state file

How state encryption works

Our solution is to encrypt the state file using a symmetric encryption key, and to lean on the OS and hardware to protect the encryption key for us. That is theoretically safe from userspace compromise.

In a perfect world, that’s a one-line change where we ask the OS to encrypt the file for us, and this blog post ends here. Sadly, there is no universal mechanism for encryption at rest for all operating systems. So we have to build something unique for each OS, with roughly the same properties.

Windows/Linux

Thanks to Windows’ latest requirements (whether you agree with them or not), TPM 2.0 devices are mandatory on most new laptops and desktops. Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs) are little hardware or firmware gadgets that are all about protecting cryptographic key material outside of the OS. You can think of them as little consumer cousins of corporate HSMs, but with a weirder and more confusing API, and more resource constraints.

There are probably a dozen people on the planet that really understand all the bells and whistles of TPMs, and I’m not one of them. Still, TPMs are the most widely available tool we have to handle state encryption for Windows and Linux clients.

There are a couple ways to encrypt data using a TPM:

- We can “seal” the data using TPM2_Create (yeah, confusing name), but that only allows up to 128 bytes, and Tailscale’s state file is usually larger than that.

- We can use the built-in symmetric encryption function

TPM2_EncryptDecrypt2(it goes both ways), but for reasons (export control?) it’s not widely implemented by TPM vendors. (Some TPM functions in the spec are optional; no, it’s not very obvious which ones) - We can encrypt the data using a symmetric key we generate outside of the TPM, then “seal” that key with the TPM. An unfortunate layer of indirection, but this is what Tailscale ended up doing for maximum compatibility.

You can see me stumbling through each of those options here.

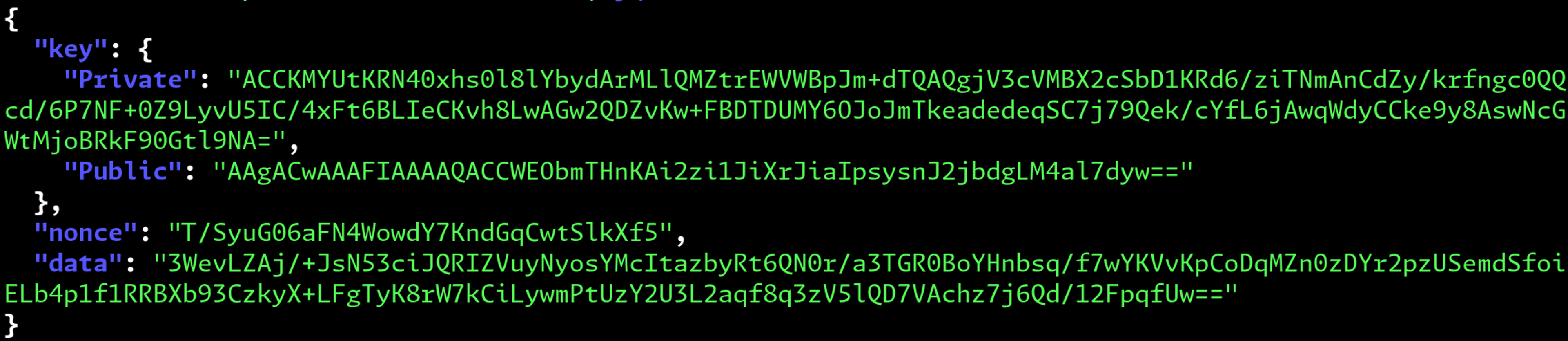

None of us at Tailscale are real cryptographers (we only pretend on TVHN), so we chose secretbox for fool-proof symmetric encryption. Secretbox requires a 32-byte private key (yay, it fits into TPM2_Create!) and a 24-byte nonce (not super secret, but should be unique so we generate a fresh one each time), so we store those along with the encrypted data as one JSON object.

One last detail for Linux: we use /dev/tpmrm0 if it’s available before trying /dev/tpm0 (these are both character devices, which is how you talk to a TPM on Linux). The former is multiplexed by the kernel for different processes. The latter can only be accessed by one process at a time. You basically always want the former.

Apple (macOS/iOS/tvOS)

Phew, that was a lot.

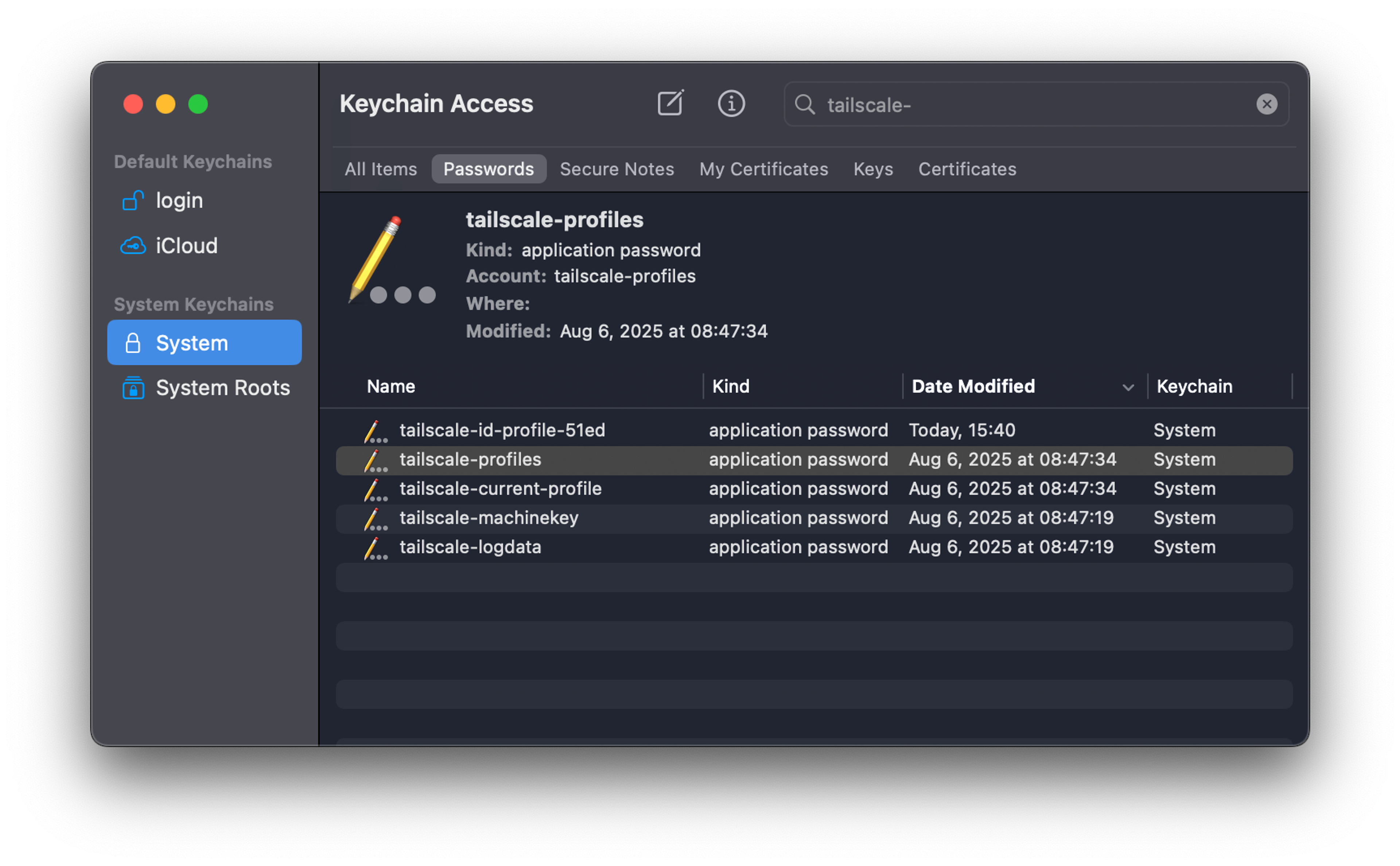

Luckily, Apple managed to create a built-in system that’s available everywhere and way easier to use: the Keychain. And while it natively supports private keys, passwords, and the like, we do the lazy thing and shove each state file field into a “password” item. If you open the Keychain app on macOS, you can see all those password entries starting with tailscale-.

The Keychain effectively does what we re-implemented with the TPM on Windows and Linux: it stores a symmetric encryption key in the hardware and encrypts the data with it, before storing on disk.

One tricky bit is that Apple actually has two different kinds of Keychains, and you can have both on the same device:

- A file-based Keychain, which is an encrypted file on disk; this was the original format on macOS

- A user Keychain, which is fully hidden by the OS, doesn’t show up as a file on disk, and is tied into the user’s login session; this was introduced with iOS

Most of the time we can utilize that second, login-based user Keychain, configuring our items to only unlock when the user actually unlocks the device. We also exclude those items from iCloud backups with kSecAttrAccessibleAfterFirstUnlockThisDeviceOnly.

On the Standalone variant of Tailscale on macOS, we use a system extension to hook into the networking stack. But system extensions are not allowed to access the user Keychain. So we have to use the “System” Keychain, which is file-based. This doesn’t reduce the level of protection for Tailscale state files, but it requires some special handling in the code, different from our other Apple clients.

Android

Android also offers a nice built-in API here for encrypted state storage: EncryptedSharedPreferences. It works exactly like all of the above, encrypting the data with a symmetric key, and protecting that key with hardware. And it has the same caveat with backups as with Keychain and iCloud: we have to explicitly opt-out. Instead of doing it piecemeal, we exclude the whole Tailscale app from backups.

You might be wondering…

What we did before 1.86

We always encrypted state files on Android and Apple platforms. It happens by default and you can’t opt-out (yay secure-by-default!).

The one exception was the standalone variant on macOS. Because of the user Keychain being unavailable to the system extension, we stored state on disk, owned by root. But we finally figured out the System Keychain approach described above in 1.86. Migrating the state for existing nodes turns out to be tricky; it even caused some trouble in 1.86.0, which we fixed in 1.86.2.

On Windows and Linux, we stored state files on disk, with tight access permissions. The thinking was: If an attacker gets the permissions necessary to read that file, they can probably fully compromise the machine in a bunch of other ways. Which is not wrong, but we can do better, at least by making lazy “smash and grab” attacks less effective.

Storing private keys in the TPM/Keychain

Yes, TPMs, Apple Secure Enclave, and Android Keystore can all store private keys and never expose them to the application. With all of those, applications only use opaque key handles, and request operations like signing and verification of signatures, but never see the actual keys themselves.

Unfortunately all of our keys are Ed25519, which is only supported by Android’s Keystore. The only widely supported key algorithms are RSA and ECDSA. And as long as we stick with standard WireGuard, we cannot change the types of keys we use.

Why not encrypt by default?

The changes in 1.86 are not on by default. This means that existing Windows/Linux/macOS devices still store plaintext keys on disk.

We’re treating this feature as Alpha, and building up some confidence in 1.86 by monitoring user feedback, to enable it by default in a future release. It’s important we get this right. If we get it wrong, your node “forgets” its state and acts as if it was a fresh install. And you wouldn’t want that surprise after an auto-update.

Additionally, there are some users who unknowingly depend on node cloning as a feature. For example, there are cases where node state was baked into virtual machine or container images with pre-approved (as in Device Approval) credentials. If those nodes suddenly started encrypting their state and failing to decrypt on another instance, that would be disruptive.

Great, I want it now!

Tailscale installed on Android, or on Apple devices from the Apple App Store, is already encrypting everything at rest, no action needed there.

On other platforms:

- macOS standalone variant: Enable the EncryptState MDM policy, or run this command from the terminal:

defaults write ~/Library/Preferences/io.tailscale.ipn.macsys.plist EncryptState true - Linux: Set the

--encrypt-statewhen runningtailscaled; typically that’s in FLAGS in/etc/default/tailscaled - Windows: Enable the EncryptState MDM policy; you can also modify the corresponding registry value manually

Once you do this and restart Tailscale, it will automatically migrate existing state to the encrypted format. If something doesn’t work right, you can undo the change, and Tailscale will migrate the state back to its original format on disk.

If you want to check whether your node is using state encryption, head to the Machines page in the admin console, select your node, and look for node:tsStateEncrypted under Attributes. You can also use this attribute in your Device Postures.

What’s next?

If we don’t spot any major regressions with 1.86, the next stable release will likely turn on state encryption by default for all new nodes. Existing nodes will keep storing their state as before, so as not to break anyone’s setup. If, for some reason, you want to opt out of state encryption being turned on in a future release, you can set the EncryptState MDM policy to false today and the future releases will respect it.

In the meantime, please give state encryption a try and tell us if something doesn’t work.

Andrew Lytvynov

Andrew Lytvynov