Like any engineer visiting family abroad, I expected to stay connected to my homelab infrastructure back in North America: accessing Kubernetes clusters, using exit nodes, managing services. What I didn't expect was just how painful that experience would become when international networks had me relying on Tailscale's default relay infrastructure.

The problem: DERP across oceans

Tailscale typically establishes direct peer-to-peer connections between devices using NAT traversal. When direct connections fail (due to restrictive firewalls, CGNAT, or other network conditions), traffic falls back to DERP (Designated Encrypted Relay for Packets) servers. DERP is Tailscale's managed relay infrastructure that also assists with NAT traversal and connection establishment.

DERP servers work reliably, but they're shared infrastructure, serving all Tailscale users who need relay assistance. They're optimized for availability and broad coverage, not raw throughput for individual connections. When you're in Delhi, India and trying to connect to infrastructure in Robbinsdale, MN, your traffic routes through a DERP server, sharing capacity with other users and subject to throughput limits that ensure fair access for everyone.

The real problem became apparent when I ran iperf3 tests. Sending all my traffic through DERP, across an ocean, resulted in severely throttled throughput averaging 2.2 Mbits/sec:

[ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate

[ 7] 0.00-1.00 sec 128 KBytes 1.04 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 1.00-2.01 sec 2.00 MBytes 16.8 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 2.01-3.00 sec 1.00 MBytes 8.42 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 3.00-4.00 sec 2.50 MBytes 21.0 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 4.00-5.00 sec 1.12 MBytes 9.41 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 5.00-6.00 sec 2.38 MBytes 19.9 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 6.00-7.00 sec 0.00 Bytes 0.00 bits/sec

[ 7] 7.00-8.00 sec 640 KBytes 5.26 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 8.00-9.01 sec 0.00 Bytes 0.00 bits/sec

[ 7] 9.01-10.00 sec 0.00 Bytes 0.00 bits/sec

[ 7] 10.00-11.00 sec 0.00 Bytes 0.00 bits/sec

...

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

[ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate

[ 7] 0.00-120.00 sec 32.0 MBytes 2.24 Mbits/sec sender

[ 7] 0.00-120.30 sec 31.5 MBytes 2.20 Mbits/sec receiveriperf3 TCP throughput test from Delhi to Robbinsdale over DERP. The wildly variable sender bitrate reflects DERP QoS shaping on the connection. The receiver total (31.5 MB over 120 seconds) tells the real story: ~2.2 Mbits/sec sustained.

The connection was barely usable for anything beyond basic SSH, despite my ISP connection testing at 30-40 Mbits/sec to international destinations under normal conditions.

Why direct connections failed

India's residential networks are notoriously difficult for peer-to-peer connectivity. Indian ISPs have adopted CGNAT aggressively due to IPv4 scarcity: Jio, Airtel, BSNL, and ACT all place residential subscribers behind carrier-grade NAT. Worse, these deployments commonly use symmetric NAT (Endpoint-Dependent Mapping), which assigns different external ports for each destination and breaks standard UDP hole punching. Combined with double NAT from home routers, Tailscale's NAT traversal simply can't establish direct connections in many cases.

What bad looks like

When I was troubleshooting my connection from Delhi, tailscale ping told the whole story:

$ tailscale ping robbinsdale-subnetrouter-0

pong from robbinsdale-subnetrouter-0 (100.69.114.112) via DERP(ord) in 463ms

pong from robbinsdale-subnetrouter-0 (100.69.114.112) via DERP(ord) in 441ms

pong from robbinsdale-subnetrouter-0 (100.69.114.112) via DERP(ord) in 478ms

2025/12/14 17:38:41 direct connection not establishedThree red flags here:

- Every ping routes through DERP: The

via DERP(ord)indicates all traffic is being relayed through Tailscale's Chicago DERP server. Why Chicago? Tailscale selects the DERP server with the lowest combined latency to both endpoints. For Delhi-to-Minneapolis traffic, Chicago (ord) typically wins because it's geographically close to my Robbinsdale infrastructure while still being reasonably reachable from India via trans-Pacific or trans-Atlantic routes. - High and variable latency: 441-478ms with noticeable jitter when it should be more consistent.

- "direct connection not established": Tailscale explicitly telling you NAT traversal failed

When Tailscale can establish a direct connection, you'll see via <ip>:<port> instead of via DERP. The fact that it never upgraded to direct—even after multiple pings, confirmed that CGNAT was blocking hole punching entirely.

Diagnosing your NAT situation

If you're experiencing similar connectivity issues, here are a few tips on diagnosing whether CGNAT and symmetric NAT are affecting you.

Detect NAT type with Stunner

Stunner is a CLI tool that identifies your NAT configuration by querying multiple STUN servers. It was written by my colleague Lee Briggs and uses Tailscale's DERP servers by default. Stunner will classify your NAT type and rate it as "Easy" or "Hard" for hole punching. If you see "Symmetric NAT" or "Hard", that's why direct connections are failing.

Tailscale's built-in diagnostics

Tailscale's client includes netcheck, which provides similar diagnostics as stunner, plus Tailscale-specific information. Running tailscale netcheck shows your NAT type, which DERP servers are reachable, and the latency to each. Look for the MappingVariesByDestIP field: if true, you have symmetric NAT, and hole punching will likely fail.

Check connection path with tailscale ping

The simplest way to see how traffic is actually flowing is tailscale ping. This shows whether your connection is direct or relayed. If you see via DERP(xxx) in the output, traffic is being relayed. A direct connection shows via <ip>:<port> instead. Run it a few times; Tailscale continues attempting NAT traversal, so later pings might upgrade to direct, even if the first one was relayed.

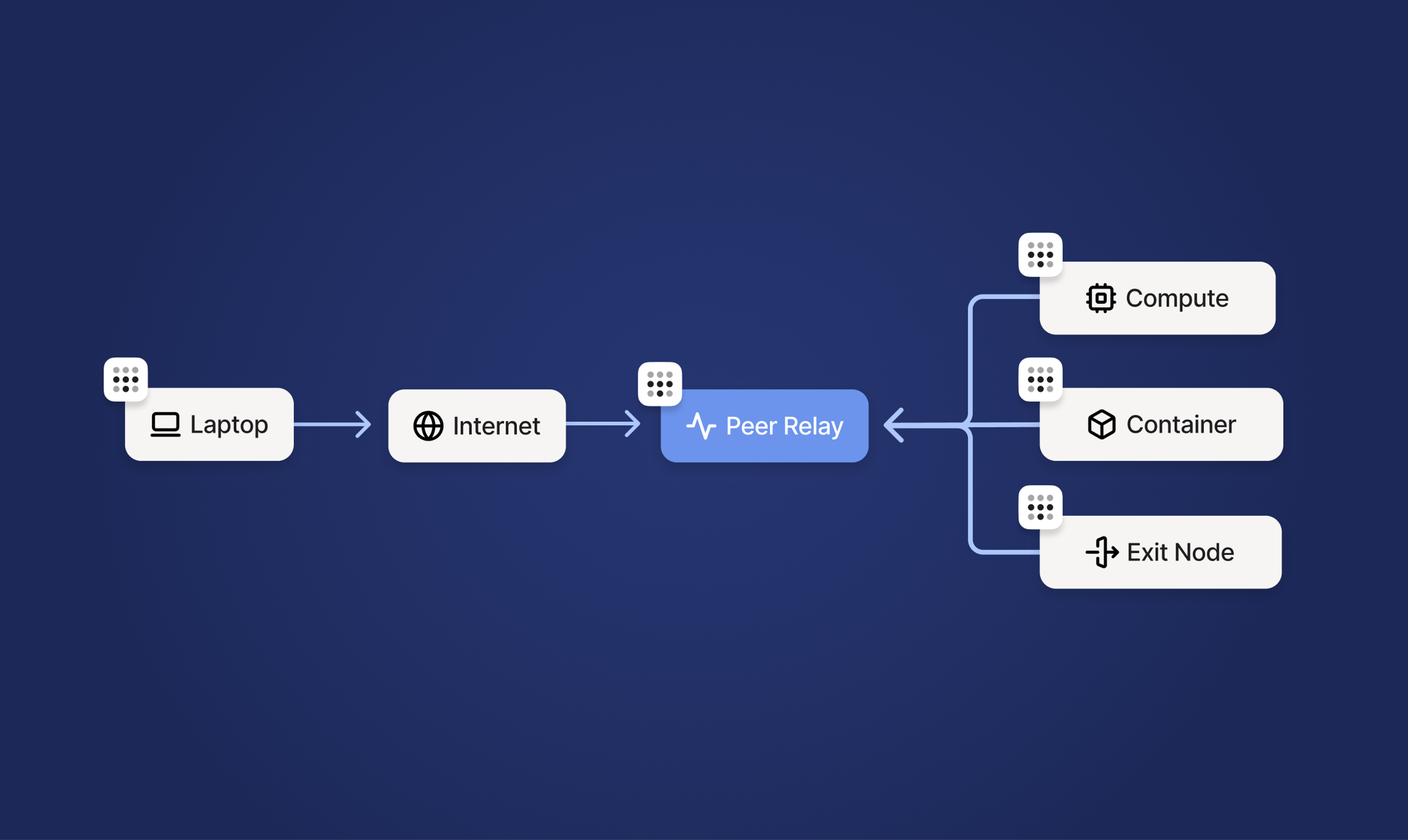

The Solution: Tailscale Peer Relays

Tailscale Peer Relays, introduced in October 2025, offer an alternative to DERP roulette: designate your own nodes as dedicated traffic relays within your tailnet. Unlike shared DERP infrastructure, peer relays give you full control over capacity: no competing for bandwidth, no QoS throttling.

How peer relays work

Tailscale Peer Relays function similarly to DERP servers but run on your own infrastructure:

- A node with good connectivity is configured as a peer relay

- When direct connections fail between other nodes, Tailscale routes through your peer relay instead of DERP

- Traffic remains end-to-end encrypted via WireGuard

- Tailscale automatically selected the best available path using this preference order:

- Direct connection (NAT traversal succeeds): preferred for lowest latency

- peer relay connection (when direct fails but relay is reachable): dedicated capacity

- DERP relayed connection (always available baseline): shared infrastructure

Under the hood, both clients establish independent UDP connections inbound to the relay node. The relay doesn't initiate any outbound connections; it simply listens on its configured port and accepts incoming traffic from peers. When Client A sends a packet destined for Client B, the relay receives it on A's connection, looks up B's session, and forwards the packet out on B's existing inbound connection. This bidirectional packet handoff happens entirely within the relay's memory: packets arrive on one client's socket and depart on another's, with the relay acting as a simple forwarding layer for encrypted WireGuard® traffic.

The critical advantage is dedicated capacity. For file transfers, media streaming, or managing remote infrastructure, peer relays remove the throughput ceiling that shared DERP infrastructure imposes.

Setting up peer relays

Any Tailscale node can act as a peer relay. For my setup, I used one of my homelabs in Robbinsdale, MN, a residential fiber connection that serves as the hub for my distributed infrastructure. The setup involves three steps:

- Enable the relay server: Run

tailscale set --relay-server-port=<port>on the relay node - Port forward on your router: Forward the UDP port from your router's public IP to the relay node

- Add ACL grants: Configure your tailnet policy to allow devices to use the relay

Opening a port might feel risky, but the relay only accepts connections from nodes in your tailnet, authenticated the same way Tailscale always authenticates peers. Random internet hosts can't use it. ACL grants control which devices can use which relays, and the relay never decrypts your traffic; it just forwards encrypted packets between nodes.

Once configured, Tailscale automatically discovers your relay's public endpoint. When the relay starts, it sends STUN probes to Tailscale's DERP servers, which respond with the public IP:port they observed. This is how your relay knows what address to advertise to other nodes in your tailnet, the same mechanism Tailscale uses for direct connection establishment.

In most cases, automatic discovery works. But if your network setup is complex (say, your router's public IP differs from what STUN discovers, or you're behind a NAT gateway), you can override discovery with --relay-server-static-endpoints to explicitly specify the IP:port combinations to advertise.

See the Tailscale Peer Relays documentation for the full setup guide.

The results: 12.5x improvement

After configuring peer relays, I ran the same iperf3 tests. The difference was dramatic:

[ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate

[ 7] 0.00-1.00 sec 3.25 MBytes 27.3 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 1.00-2.00 sec 3.50 MBytes 29.4 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 2.00-3.00 sec 4.12 MBytes 34.6 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 3.00-4.00 sec 3.88 MBytes 32.5 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 4.00-5.00 sec 4.25 MBytes 35.7 Mbits/sec

...

[ 7] 58.00-59.00 sec 3.75 MBytes 31.5 Mbits/sec

[ 7] 59.00-60.00 sec 4.00 MBytes 33.6 Mbits/sec

...

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

[ ID] Interval Transfer Bitrate

[ 7] 0.00-120.00 sec 396 MBytes 27.7 Mbits/sec sender

[ 7] 0.00-120.26 sec 394 MBytes 27.5 Mbits/sec receiverSame test, same location, peer relays enabled. Throughput stabilizes at 27-35 Mbits/sec, a 12.5x improvement over DERP.

Results comparison

The peer relay test showed consistent 27-35 Mbits/sec, with no sustained dropout periods.

Verifying peer relay connectivity

You can verify your peer relay connections are working using tailscale ping. Here's what the upgrade from DERP to peer relay looks like in real-time:

$ tailscale ping robbinsdale-subnetrouter-0

pong from robbinsdale-subnetrouter-0 (100.84.40.24) via DERP(ord) in 452ms

pong from robbinsdale-subnetrouter-0 (100.84.40.24) via peer-relay(67.4.225.236:7777:vni:619) in 306ms

pong from robbinsdale-subnetrouter-0 (100.84.40.24) via peer-relay(67.4.225.236:7777:vni:619) in 298msThe first ping routes through DERP (Chicago) at 452ms. By the second ping, Tailscale has established the peer relay path, and latency drops to 298-306ms and stays consistent. The vni:619 is a Virtual Network Identifier that isolates this relay session.

Understanding the baseline latency

To put these numbers in context: the Delhi-to-Minneapolis route typically averages 280-320ms under good internet conditions. No direct submarine cable exists between India and the United States, so traffic routes through Singapore, the Middle East, or Europe before crossing the Atlantic or Pacific.

The 298-306ms peer relay latency aligns with the expected baseline for this route. The latency improvement over DERP (452ms → 298ms) comes from skipping the extra hop through Chicago, but that's a minor win. The ~150ms latency reduction is nice; the 12.5x throughput increase is transformative.

Conclusion

Peer relays transformed my holiday connectivity from barely usable to genuinely productive. Instead of frozen terminals and failed file transfers, I could manage my homelab almost as efficiently as if I were back home.

If you've hit DERP's throughput limits, peer relays are worth exploring. The setup is minimal (designate a node, open a UDP port) and you get full bandwidth on infrastructure you control. DERP remains the reliable fallback, but when you need sustained throughput, peer relays fill that gap.

Raj Singh

Raj Singh