A recent Reddit thread noted that Tailscale's uptime has been, uh, shakier than usual in the last month or so, which included the holiday season. I can't deny it. We believe in transparency, so we have our uptime history available on our status page that will confirm it for you.

We are committed to visibility which is why we maintain this public uptime history page. But one challenge of maintaining visibility is it can leave our status updates open to a wide range of interpretations or assumptions. When we say, "coordination server performance issues," is that an outage, or is it just slow? Does it affect everyone or just some people? If Tailscale's coordination service is down, does that mean my connections are broken? And when you say "coordination server" … wait ... surely we run more than one server?

Great questions, and the answers are all kind of tied together. Let's go through them. We don't get enough chances to talk about our system architecture, anyway.

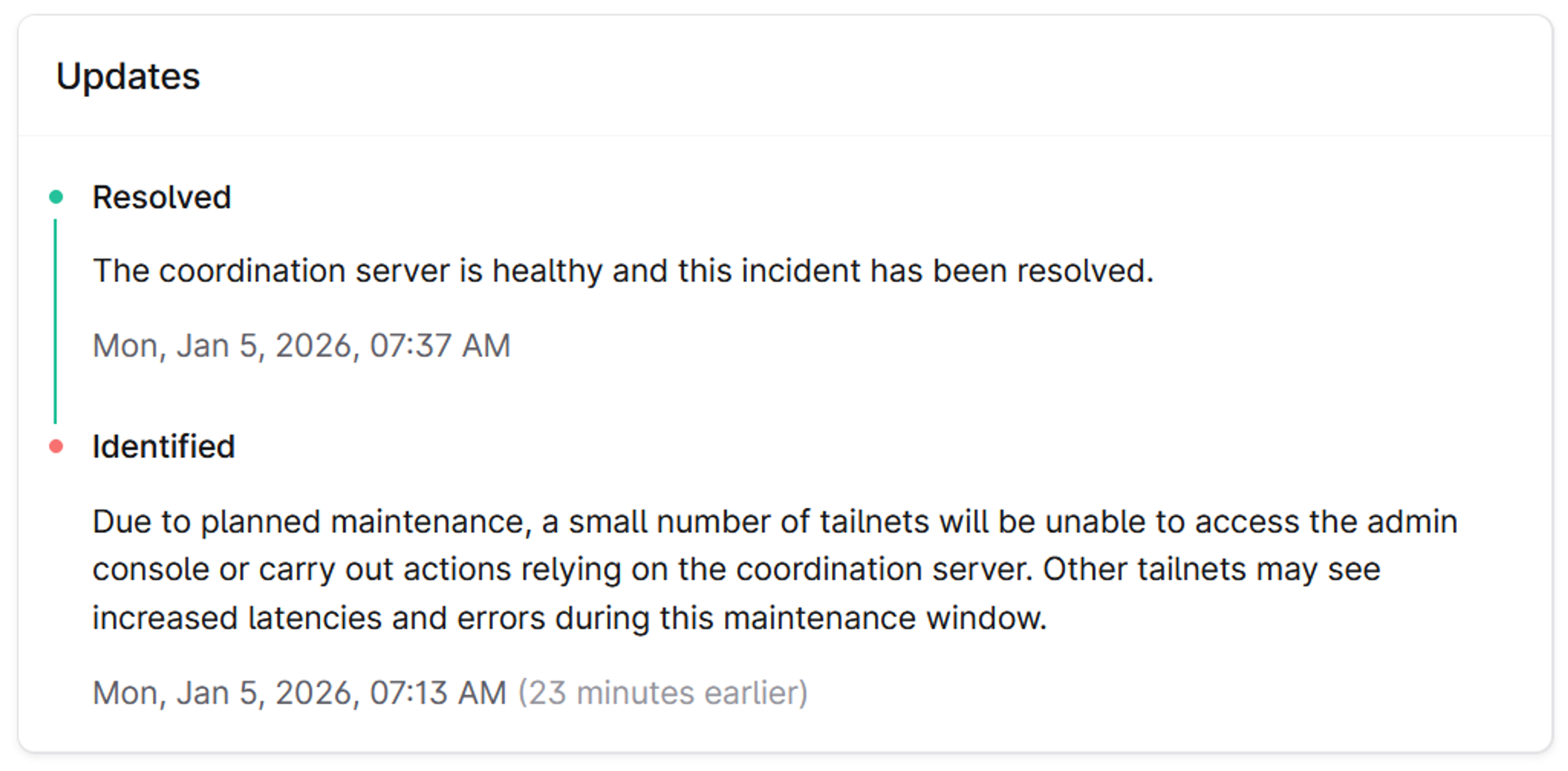

First of all, the history section of the status page actually has more detail than it seems at a glance. Despite the lack of visual affordances, you can click on each incident to get more details. For example, this incident from Jan 5:

Looks like whatever happened took 24 minutes, and affected a small number of tailnets, but it still caused increased latency and prevented some people from carrying out actions. That’s disruptive, and we’re sorry. If you’re wondering why there wasn’t an advance notification, here’s the context. We detected an internal issue early, before it caused user-visible impact, and intervened to repair it. Part of that repair required briefly taking a shard offline, which created a short period of customer impact.

Part of engineering is measuring, writing down what went wrong, and making a list of improvements so it doesn’t go wrong next time. Continuous improvement, basically.

To be clear: this was an outage, and we’re not trying to downplay it. The difference here is in the shape of the failure. Thanks to many person-years of work, it was planned rather than accidental, limited to a small number of tailnets, and for most other tailnets primarily showed up as increased latency rather than broader unavailability. We also resolved it faster than similar incidents in the past. Continuous improvement means measuring blast radius, severity, and time to recovery, and steadily improving them, even as we continue to scale.

Tailscale's architecture

We probably should stop referring to a "coordination server" and start calling it a "coordination service." Once upon a time, it was indeed just one big server in the sky. True story: that one big server in the sky hit over a million simultaneously connected nodes before we finally succeeded in sharding it, or spreading the load across multiple servers. As computer science students quickly learn, there are only three numbers: 0, 1, and more than 1. No servers running, one big server, or lots of servers. So now we have lots of servers.

But, unlike many products where each stateless server instance can serve any customer, on Tailscale, every tailnet still sits on exactly one coordination server at any given moment (but can live migrate from one to another). That's because, as we realized maybe five years into the game, a coordination server is not really a server in the classic sense. It's a message bus. And the annoying thing about message buses is they are annoyingly hard to scale without making them orders of magnitude slower.

That thing in Tailscale where you change your ACLs, and they're reflected everywhere on your tailnet, no matter how many nodes you have, usually in less than a second? That's a message bus that was designed for speed. Compared to classic firewalls that need several minutes and a reboot to (hopefully) change settings, it's pretty freakin' awesome. But, that high-speed centralized (per tailnet anyway) message bus design has consequences. One of the consequences is, when the bus eventually has any amount of downtime, no control plane messages are getting passed, for the nodes connected to that instance.

We knew this when we started, so we designed around it. No matter how resilient or distributed or CAP theorem or Unbreakable or “Nobody Ever Got Fired For” your architecture is, sooner or later your client devices get disconnected from it. Maybe they fall off the internet temporarily. Maybe your home Wi-Fi router reboots. Maybe your DNS server goes down. Or yes, maybe the coordination server instance you're assigned to has an outage. Speaking of CAP theorem, that's the “P”: network partitioning, i.e. the client and the server can't talk to each other.

When that happens, most SaaS products just stop working. If you're lucky, they pop up an error message that blames you for not being online or whatever. What does Tailscale do? In steady state: nothing special. Every Tailscale node caches its node state in memory, and its list of peers, and the list of locations of the peers, and their DERP servers. If the coordination server goes down, that cache can't be updated. But all your existing connections keep working, and also all the other parts of the data plane keep working. (There's also one element of regional routing failover that requires the control server right now; we're working on removing that dependency.)

The only things that don't work when the bus is down are adding/removing/changing nodes and packet filters. That's what we mean by "actions relying on the coordination server." Control plane stuff. Want to change your network? Coordination server. Want to use it? No coordination server.

If your home Internet goes down but your home Wi-Fi is still working, your phone and your computers at home can still talk to each other over Tailscale. They can't reach the control server, but the data plane keeps on going.

The upside of our architecture is that many incidents don’t break existing connections: the data plane usually keeps flowing even if the control plane is having trouble. The downside is that the people who do hit the control plane at that moment—trying to log in to the admin console, approve a device, or change an ACL—can be blocked entirely, and that’s a big deal.

With millions of users, even a limited-scope incident will show up quickly: someone runs into it, checks the status page, and posts about it. That doesn’t mean it’s “just noise”, it means the impact is real for a subset of customers, and we need to treat it that way while we keep shrinking both the blast radius and the duration.

(As they grow, companies often split their status dashboard so that individual customers can see when they were affected. We're at that awkward size where we're mature enough to track the outages, but not so big that splitting it makes sense yet.)

Continuous improvement

It’s true that many outages don’t sever existing connections—that’s a deliberate part of the design. But if you happen to need the control plane during those minutes, you feel the outage at full force.

That’s not acceptable. Tailscale is critical infrastructure for a lot of organizations, and we have to earn that trust by making these incidents rarer and shorter.

So what are we going to do about it? Well, a few things.

First of all, there's a limitation in Tailscale nodes' ability to work when their coordination server is offline. That limitation is, if your Tailscale client software stops and then restarts, it forgets its network map and falls off the network. This counts as "adding or removing a node," which is one of those actions you can't do. But we've found a way around it. We're working on a feature that caches the network map between runs. That way, if Tailscale restarts, you're right back where you were. As a bonus, even when the control server is working fine, this caching can shave a few tens or hundreds of milliseconds off your time to first packet in highly dynamic situations like CI/CD and tsnet apps.

Second, we're evolving our sharded coordination service to reduce disruption. Hot spares, better isolation, auto-rebalancing, live migrations, that sort of thing. A control plane for our control plane.

Third, we’re investing in better multi-tailnet sharing. This is a longer-term piece of the roadmap, but it matters for reliability because it lets you structure networks around geography without losing the ability to share resources cleanly. For example, if you have a lot of nodes in AWS us-east-1, you might want their coordination close by to reduce the chance of a network partition. But if you also have a lot of nodes in us-west-1, hmm, you wish the coordination server were there too. And, and … and, this will work if you slice your tailnets by region, if only you could share nodes en masse between tailnets. That's coming, over time. When it does, we're really going to see why this “centralized” message-bus architecture is so good.

Fourth, we’re just plain making the software better and more mature every day. More quality gates, more automated testing, more integration testing, more stress testing. Fewer and fewer reasons to have downtime in the first place. As we keep scaling, this kind of work never really stops; it’s a continuous investment in making the system more resilient.

Let's keep growing

I'm not gonna lie to you. None of us are proud of having (counts on fingers) nine periods of (partial) downtime (or maybe slowness) in one month. Even though almost all were resolved in less than an hour. Even though your data plane kept going. Because, well, that's who we are. And who we are is a team that would rather over-communicate than under-communicate. Even when an incident is brief or affects only some customers, we want it to be visible and explained.

We're going to keep counting every single small outage and measuring it and fracturing it into two smaller outages and eventually obliterating it, one improvement at a time. That's just how it's done.

If you notice an outage, please report it using this form. We hope there isn’t one, but your report helps us improve Tailscale. And if reading posts like this makes you think “I want to help fix that,” we’re hiring; our careers page is here.

Avery Pennarun

Avery Pennarun